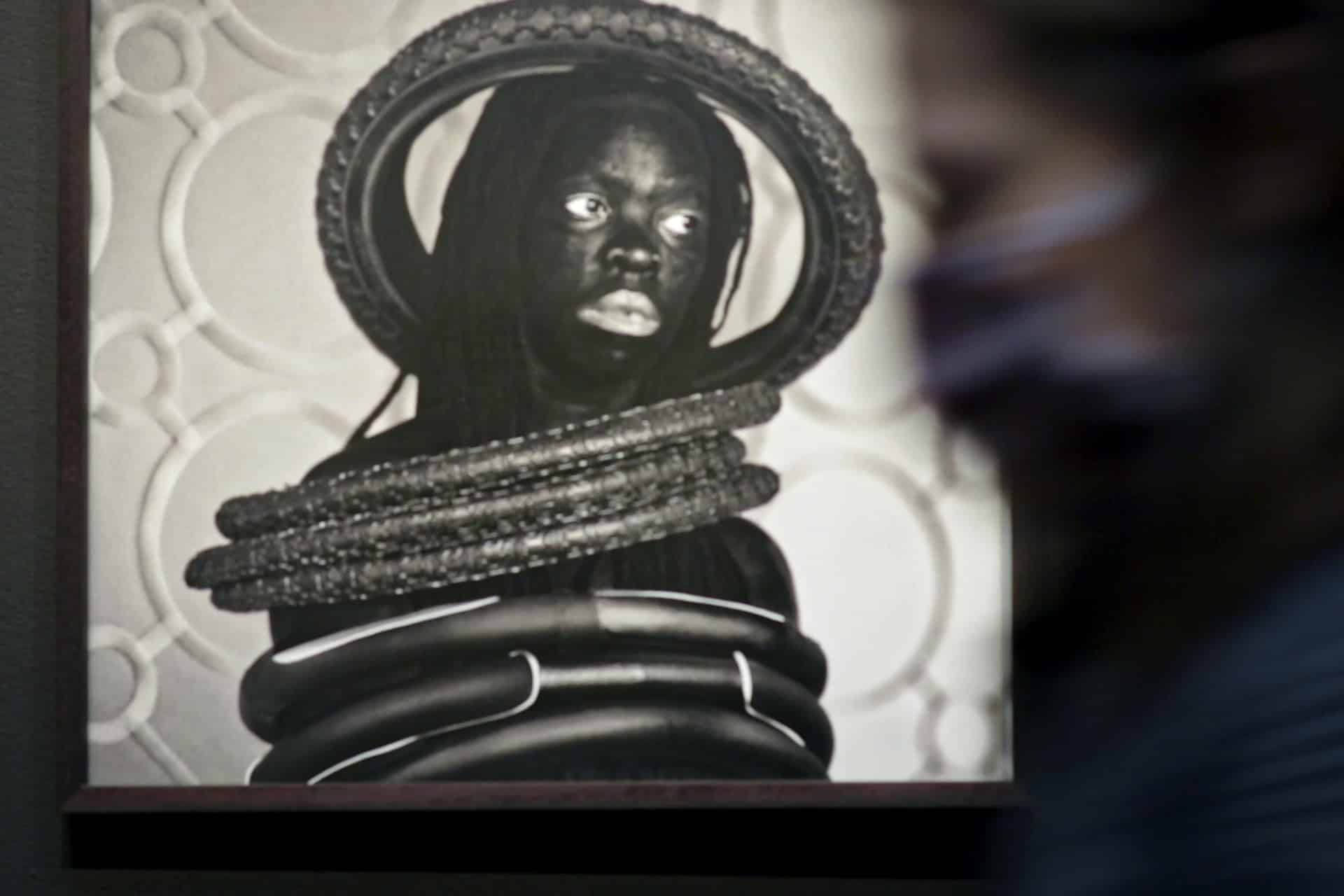

//A visitor walks past a self-portrait of the artist and activist Zanele Muholi at the Center for Visual Art, MSU Denver on Feb. 18. Their work is on display at CVA until March 20. Photo by Polina Saran | [email protected]

Zanele Muholi is not exactly an artist—they prefer the title visual activist.

Muholi’s exhibit, Somnyama Ngonyama: Hail the Dark Lioness, celebrates visual activism through the lens of race, gender and culture. The exhibit is being held at the Metropolitan State University of Denver’s Center for Visual Art until March 20. In light of March being Denver’s month of photography, Muholi’s artwork relays an important message to Denverites regarding agency and representation at a time when injustices are being reckoned with.

Through more than 80 self-portraits, Muholi, who uses they/them pronouns, uses their body as a visual confrontation to identity politics and the division it causes within the Black and LGBTQI communities. The collection features photos taken between 2012 and 2019 in cities like Philadelphia, Paris and Cape Town. Organized by Autograph and curated by Renée Mussai, CVA Director Cecily Cullen said the CVA is proud to host the globally celebrated collection.

“So much of portraiture that is collected by museums has focused on white subjects, so creating this really extensive body of work that features people who’ve been left out of the visual archive for so long is the main thrust of [Muholi’s] work,” Cullen said.

Bringing the collection to her museum was years in the making. When Cullen first came across the traveling exhibition, it was fully booked. After persistent negotiating with Mussai and Autograph in London, she secured a contract about a year and a half ago. Even though COVID-19 made it uncertain, the exhibit still arrived on time for Denver’s month of photography.

“My practice as a visual activist looks mainly at Black resistance [and] existence, as well as insistence,” said Muholi in an interview with Mussai. “Most of the work I have done over the years focuses exclusively on Black LGBTQI people, making sure we exist in the visual archive.”

As a South African citizen, Muholi uses their work to confront hate crimes extant in mainstream media. Even though apartheid was abolished in 1994, the ghost of the period lingers today. Muholi recognizes the production of their work would have been impossible three decades ago, which is why they continue to challenge the generational distortion of Black bodies in the hopes of inspiring a lasting change.

In fact, Muholi’s self-portraits demonstrate their attempt to reclaim Blackness. Aside from their work in visual mediums, Muholi is the co-founder of the Forum for the Empowerment of Women, an organization devoted to promoting rights for Black lesbians in South Africa. They also founded Inkanyiso, which houses queer visual media as a form of activism. Their full career to date, with over 260 photographs, is currently held at Tate Modern in London.

Cullen hopes students and visitors to the CVA understand the depth of Muholi’s work, which she emphasizes is not only rich in content but aesthetically masterful.

Cullen designates “Julile I, Parktown, Johannesburg, 2016,” titled in one of the official languages of South Africa, isiZulu, as one of her favorites from the series. The portrait is about 10 feet wide and 5 feet tall. In the photo, Muholi is lying on the floor, unclothed, clutching inflated plastic bags that, at first glance, look like pillows. Stacks of newspapers hold space behind their naked silhouette. Bright white eyes contrast beautiful dark skin, an incongruity masterfully amplified in post-production to create a strikingly intense gaze directed at the viewer. The newspapers emblematize media and propaganda, speaking to their powerful capacity to alter public perception. The portrait asks the viewer to be critical, Cullen notes.

“I think it’s important for us in the United States to [not only] look at our laws and policies, but the actuality of how we treat each other,” Cullen said. “Just in general, there’s a lot of parallels between South Africa and the United States and the racism and gross inequality.”

While Muholi utilizes visual mediums as activism, Susan Sontag, the American writer and political activist, analyzes them. In Sontag’s book-length essay, “Regarding the Pain of Others,” she discusses the “they” versus “us” construct and its implications on world power dynamics. She explains how the mainstream media’s modern mandate to entertain, not just inform, skews the reporting of outsiders’ stories to fit the entertainment mold. She calls such distortion of truth not only inaccurate but unethical.

All of this is why Muholi says they produced this photographic document—to encourage people to be brave enough to occupy spaces without fear of being vilified for owning their own narrative. They chose to be the sole subject of the work to prevent putting someone else’s body through the scrutiny and vulnerability the medium requires.

Muholi adopts various personas to debunk stereotypical tropes commonly used against gender-nonconforming and BIPOC individuals. They use found objects, ranging from cable ties to rubber tires, to invoke themes of social brutality, environmental issues and cultural violence, among many others.

Local artist Jasmine Wynter echoes these sentiments in her own work. Her series, currently held in the CVA’s Deeper Than Skin 965 Project Gallery and titled “Shades of Black,” is adjacent to Muholi’s collection. She says her work is a medium intended to create space for people to address the world that Black adolescents live in.

“[Muholi’s] photographs present a means to evoke the complex and intricate presence of the African body and soul,” Wynter said. “There is a blend of intersectionality of that within the LGBTQ+ community and what that looks like for those who find themselves within Blackness and in a non-heteronormative space. While the concepts of what we are focusing on diverge, inadvertently they link between the African and Black existence both having to communicate and validate their existence through its people.”

Wynter says Denver is heavily influenced by Blackness, both historically and contemporarily. She emphasizes that the city, like most places within the United States, is socially fashioned in a manner that is uncomfortable for anyone who doesn’t fit the “normative mold.”

“The significance of this exhibition is that it unpacks not only Blackness in how it has been mistreated, misrepresented and manipulated, but how it thrives beyond any comprehension of what it has been told to be,” she said. “This serves as a reminder for Denver and Colorado as a whole the ever-potent presence of Blackness.”

Learn more at msudenver.edu/cva.

Video below by Polina Saran.

0 Comments