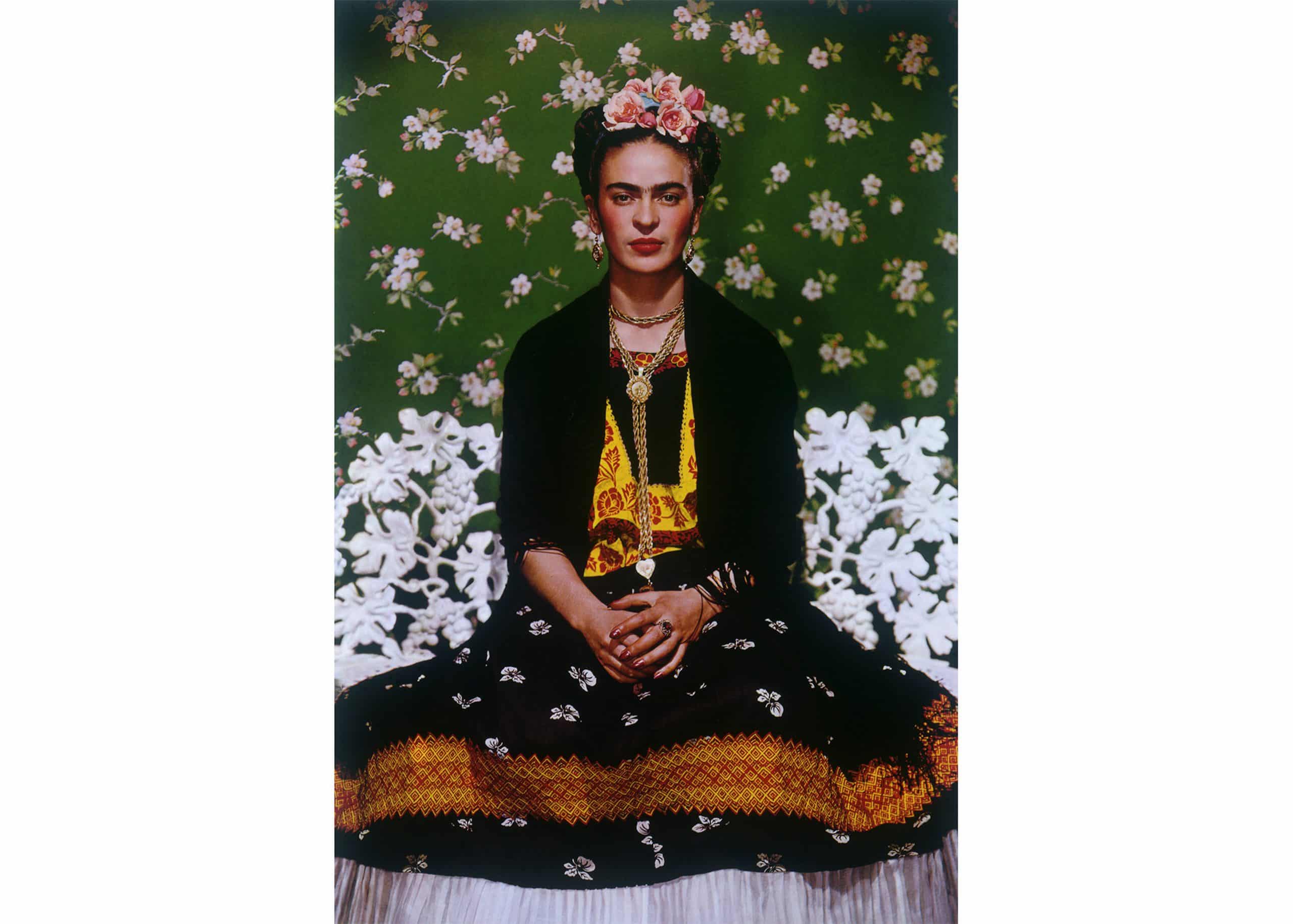

//Nickolas Muray, Frida on White Bench #5, 1939

Upon entering the Frida Khalo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism exhibit at the Denver Art Museum, you realize that this is not a shrine to Kahlo and her pop-culture status. Rather, you’re invited to explore the story of a people evaluating their collective identity between tradition and imperialism, art and war.

With 29.9% of Denverites, roughly 217,436 individuals, identifying as Hispanic and a need for racial reckoning extending beyond 2020, the exhibition offers a link between Mexican Modernists and Coloradans.

The gallery will end its four-month run on Jan. 24, but Latinx art inspired by the Mexican Modernists will remain throughout the streets of Denver. Muralists like Carlos Frésquez looked to Mexico in order to study public education through art.

“A lot of the people were uneducated and [Mexican Modernists] used these murals to educate people, to tell their history, to tell their story, to tell the past and the present and even the future,” Frésquez said. “I was educated not only formally through school but through my own investigations of looking back at these Mexican muralists: Rivera, Siqueiros, and Frida.”

Frésquez and other Chicanx muralists went on pilgrimages to Mexico to study with Rivera and Siqueiros. Mexican muralists encouraged Chicanx artists to bring education through public art back home to the U.S. during the Chicano Movement.

This complex history and Colorado’s diverse population was highlighted during the exhibit’s opening ceremony, which included Berenice Rendon-Talavera, Consul General of Mexico for Colorado.

“For the public in general, [the exhibit] will be a great opportunity to have an encounter with Mexican arts, but also the historical process in our country,” Rendon-Talavera said. “For the Mexican community, it will be a great opportunity and great pride that we will admire and appreciate these works here in Denver.”

The first large piece is Rivera’s famous “Vendedora de Alcatraces,” or “Calla Lily Vendor.” Section introductions tell viewers the painting reveals the opulence of the land and an appreciation for tradition.

Even the section description is reminiscent of pre-Hispanic traditions. Becky Hart, curator of modern and contemporary art for DAM, worked with Hector Esrawe and Ignacio Cadena, designers from Mexico City, in order to reflect Mexican styles of design in the lettering and gallery layout.

“We are a cultural institution that is predominately white,” Hart said. “Our curatorial team had four Latinos on it but I felt that it was important that we worked with Mexican people that had equal input and agency.”

DAM has highlighted Latinx art in the recent past with the 2017 Mi Tierra: Contemporary Artists Explore Place. However, Mi Tierra broke a twenty-year drought without a Latinx-centered exhibit, which is surprising, considering Colorado was once a part of Mexico.

“The name of our state is Colorado, it’s a name in Spanish. We have this history here, we have such a big population and so [the exhibit] shows that we are here and we are relevant,” said José Quintana, a professor in Metropolitan State University of Denver’s Department of Chicana/o Studies.

Quintana teaches Chicanx culture and cuisine and asks students to define Mexicanidad, or Mexican-ness, for themselves free from imperial thought. He highlights the word “mestizo,” once a derogatory term meaning “mixed blood.” The word was used as a rung on a European-enforced caste system placing Spanish colonizers at the top and indigenous Mexicans at the bottom. Quintana hopes that through rejecting this lingering thought system, he can invite a new positive definition of mestizo—a true merging of cultures.

When speaking to his students, Quintana highlights the fact that the Mexican revolution was violent but also cultural. Colonizers had sought to erase indigenous identity. Artists used public murals to re-educate the masses on their buried indigenous history.

“Both Diego and Frida in their artwork were really specific on which foods they used because they knew it was connected to their Indigenous and Mexican past,” Quintana said. “They didn’t want to include any of the European elements because they wanted people to celebrate that unique Mexican-ness that had been lacking for the last 400 years because it was dominated by a European, Euro-centric mentality.”

One of such artworks currently at DAM is Rivera’s mural titled “Man at the Crossroads,” which centers the importance of indigenous crops. Rivera, along with other Mexican communists, found canvas paintings to be bourgeois, hung in museums where only the wealthy could access them. Rivera led the front in creating public art.

The show itself isn’t without its own ironies. Khalo not only expressed negative feelings about the U.S. but was also a communist. The gift shop plastering her face on overpriced handbags would draw at least a balk from the artist, not to mention the $26 admission ticket.

For the Coloradans who can’t afford luxuries during record unemployment, there are online options. For patrons pinching pennies or wary of the risk of COVID-19, the museum’s website has videos and resources to learn about the exhibit. Most of them are free.

However, Denver has other free options that connect residents to the legacy of Rivera’s public murals. Artists like Carlos Frésquez have spent their lives coloring Denver with the history of the Chicanx people that called Colorado home long before it was a state, some as far back as 1598 B.C.E.

Lucha Martinez de Luna runs the Chicano/a Murals of Colorado Project that works to preserve murals including those of her father, Emanuel Martinez. As a part of DAM’s online resources, Martinez de Luna presented a webinar on Jan. 5 speaking to the importance of appreciating murals throughout Latinx history.

“Coloradans have not been able to have that opportunity to make that link between Mexico and the Chicano artists here,” Martinez de Luna said.

As a member of the Latino Audience Alliance at DAM, Martinez de Luna has advocated for exhibits contextualizing the work of Chicanx muralists. She hopes that through this consideration, all Coloradans will work to protect other Latinx art.

As recently as Sept. 20, new tenants to a building on 8th avenue whitewashed a mural titled “Huitzilopochtli” or “Hummingbird Warrior” by Denver Artist David Ocelotl Garcia, whose work is displayed at La Raza Park.

Martinez de Luna is working with the city and state government to find ways to protect these murals. The CMCP encourages the public to educate themselves while visiting murals throughout the state with their online map and show appreciation by visiting DAM.

Despite public health concerns, tickets to Mexican Modernism have sold out quickly. Exhibit visitor and local amateur artist Alba Valerdi, who identifies as Mexican-American, has highlighted Kahlo in her own work and was pleased to see a piece of Mexico in Denver.

“Denver has a very large Latino population, and representation matters,” Valerdi said. “It’s nice to have an exhibit we can relate to, and learn more about our motherland.”

A family tree with female Mexican artists on the branches and Frida as the trunk is the first thing you see upon entering the final section of the exhibit. Above, a quote from Rivera reads, “A life contains the elements of all lives.” Quiet guitar strumming plays as draped fabric and careful lighting reminiscent of sunlight streaming through leaves fill the space as one last painting of Khalo and Rivera look back at you.

We hope you enjoyed this article! Did you know you can support your local press for FREE by becoming a member? Subscribe today.

0 Comments