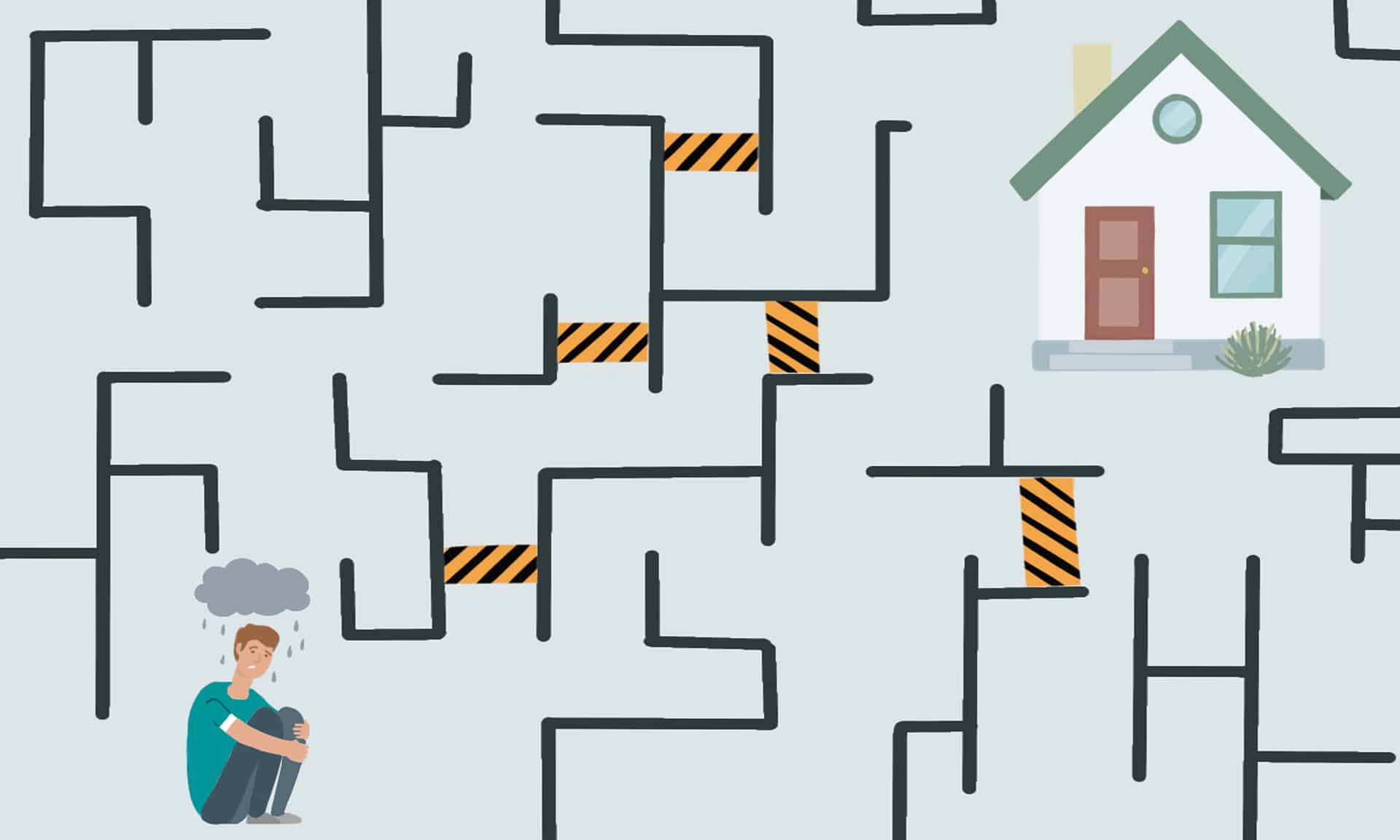

//The obstacles that kids in the foster care system already faced before the pandemic have become even more substantial. Illustration by Madison Lauterbach | [email protected]

Editor’s note: Some sources in this story are referred to by initials or pseudonyms to protect their identities.

Wrapped up in a gray fleece blanket with her back against the bottom bunk bed, 14-year-old T tucked her hair behind her ear, looked away from the computer camera, and worked hard to hold back tears as she carefully and quietly shared what life is like in foster care during a global pandemic.

“Starting at a new school, remote learning, I know no one. It’s been completely awful,” T said. “The isolation of not being able to leave the house, because that’s what my dad did. He would isolate us from the world. So, this year is just one real big trigger.”

Separated from her grandparents, the closest family she has, T is confined to the walls of yet another foster home and faced with spotty Zoom sessions with teachers. She is consumed with panic attacks, endless fear and intense worry during her freshman year of high school.

“Being in foster care for teens is hard with or without a pandemic. But add a pandemic, and it gets a whole lot harder,” T said. “I used to go to school and have panic attacks and not tell anyone about it, but now, my foster parents see the panic attacks. They see the trauma fits. What if this placement falls through? Who is going to want me then?”

T is one of 4,100 children and teenagers currently in the state foster care system, according to data collected from the Colorado Office of Children, Youth and Families. After suffering years of abuse and neglect at her parents’ hands, she was removed from her home by police and placed into foster care because of the ultimate crime.

“How am I supposed to go to school and function like a normal person who has just found out her brother was killed by her dad? The one who was supposed to love her,” said T.

Since her sibling’s death, T has spent time grieving and advocating for herself. She said the pandemic has made it even more difficult to feel support from the foster care system since visits with caseworkers have been online or cut short.

“Caseworkers visit once a month for barely an hour, and they see everything perfect, and nothing’s wrong because they’re here,” T said. “I wish they would listen as they would listen to their own child. How are we supposed to feel safe in a system that won’t listen to us and help us when we ask?”

Foster parents feel that COVID-19 has made their job harder as well, according to a longtime foster couple who spoke under the condition of anonymity.

“You kind of lose a sense of yourself when you foster. You lose control over your schedule and your life. COVID only magnified that for us,” the foster mom said.

Six months before the virus hit, the two full-time workers welcomed a baby boy into their home who had been removed from his parents’ care for reasons related to drugs. In an attempt to reduce the spread of the virus, the system pushed to pause parental visits indefinitely. However, the foster couple fought to keep the visits on schedule.

“I, personally, kind of forced it. Like, I’m not going to stop having visits. There’s no reason to. It will do nothing but hurt their bond. And I know that wasn’t a possibility for a good majority of the kiddos in foster care,” the foster mom said.

From visitations to placements, court hearings to parental recruitments, the entire foster care system has been impacted by the COVID pandemic, according to Joe Homlar, the Child Welfare Director for the Colorado Office of Children, Youth and Families.

And that impact is expected to carry on as funding issues mount across the state of Colorado.

“We’re planning to continue our work with fewer funds next year. I know these cuts can be tough, but I know they are also temporary,” Homlar said.

Renee Bernhard knows that it will be a difficult feat. She’s committed to offering help through her organization, Foster Source.

“The counties are overwhelmed. They’re low on funding, they’re low on people, and they’re low on resources,” Bernhard said.

COVID made that glaringly clear as caregivers tried to manage trauma parenting, remote learning, remote visitations and remote therapy for kids on top of their jobs. The unprecedented stressors left some foster parents feeling helpless and ready to give up.

“We saw veteran foster parents experiencing behavior they had never seen in their 15 years of fostering,” Bernhard said. “Early on in the pandemic, counties were calling me and saying we need help. Foster parents want to disrupt—which means they’ve called the county and said please come and pick up the child—and we just can’t let that happen.”

To prevent further disruptions and avoid additional placements within the system for the foster children, Foster Source sponsored and matched 50 families across the state with mental health therapists to hold weekly virtual sessions. Still, help will be needed long after the pandemic is over.

Foster Source is expecting an increase in the need for foster parents as schools return to in-person learning. Teachers are mandatory reporters and are required by law to report suspected child abuse and neglect.

“Referrals will increase drastically. Most child welfare referrals come from teachers, so when we’re online, and teachers can’t see the children or children just aren’t there, nobody can report potential abuse. Referrals are going to go up. We will need more foster parents.”

Last spring, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security, or CARES Act was passed in response to the economic fallout in the wake of the pandemic. The bill was a $2 trillion package to aid families, schools and businesses. The CDHS Division of Child Welfare received $714,583 in CARES Act funding and distributed it to each county. Denver County was allocated $97,094 to be used to secure things like personal protective equipment. The money only went so far and left some group homes housing foster teens in between placements vulnerable to the virus.

A Denver first-time foster parent who chose to remain anonymous was placed with a teen who contracted COVID after being placed in a group home.

“She was quarantined, alone and isolated. They weren’t wearing masks, and they weren’t taking precautions. No wonder she got it.”

Months after her COVID diagnosis, the teen still has no sense of smell and taste. The group home was one of four placements in the past year she’s been through as she works to terminate her parents’ rights due to neglect, physical abuse and substance abuse.

“Teenagers are really, really the hardest hit, I think, by the system, and sometimes the most underserved,” the foster mother said. “If you’re a teenager and you’re in the system, a lot of times the plan is to age out, and services and resources shut off immediately when you turn 18.”

In 2019, according to Children’s Rights, more than 17,000 young people aged out of foster care without permanent families. Research has shown that those who leave care without being linked to forever families have a higher likelihood of experiencing homelessness, unemployment and incarceration as adults.

T hopes her current foster parents adopt her, but she fears, due to the pressures of the pandemic, nothing is certain.

“We really just want someone to love us because our parents can’t love us.”

If you are concerned about the safety and well-being of a child, call 844-CO-4-Kids.

We hope you enjoyed this article! Did you know you can support your local press for FREE by becoming a member? Subscribe today.

0 Comments